HABITS AND HABITAT ESSAY

Introduction

Performance Space is delighted to present this new photomedia installation by NSW-based artist duo Patrick Ronald and Shannon McDonell.

Since moving to the CarriageWorks in 2007, we have commissioned works for the foyer area that have resonated with the site and its histories, or in this case, have juxtaposed a different kind of place and scale against its industrial architectures.

As a multidisciplinary organisation with a national focus, we are pleased to be working with contemporary artists who choose to work outside of the normative centres for cultural activity, bringing different perspectives into our program.

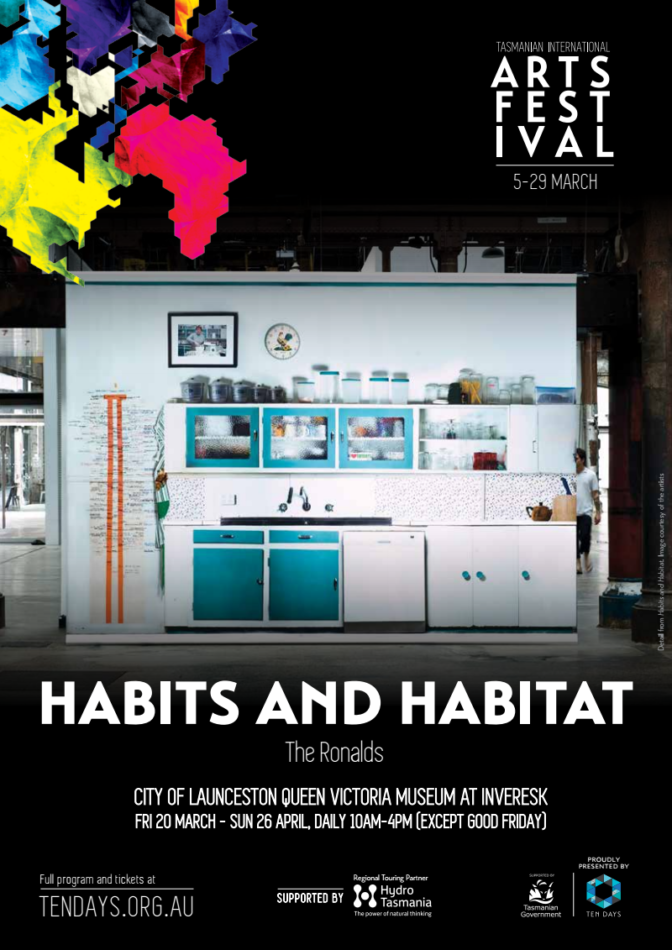

Ronald & McDonell’s Habits and Habitat offers visitors the opportunity to become part of a constructed scene and to take a voyeuristic look into another person’s home.

Through painstaking detail, the project investigates cultural transfer, the connection (and disconnections) between country and city, and the ways that the ‘bush’ continues to inform Australian culture and identity.

Daniel Brine, Director, Performance Space

HABITS AND HABITAT

Jean Baudrillard began Simulacra and Simulation by referring to Jorge Luis Borges’ tiny paragraph-length fable about an unnamed empire that sought to represent its territory with a 1:1 scaled map as a “second-order simulacra”.1 No longer even useful as an inversion, Baudrillard used the fable as a spring-board to leap into notions of the Hyperreal: of simulation without territory and origin, without doubling and mirroring.2 But is Borges’ fable entirely useless if it is applied to place and temporality? The representation of empires on the cusp of change and disappearance? While the exact map could never stand for place itself, it could certainly show us a semblance of what once was. The drive to represent, however, would be borne of different motivations perhaps, more akin to certain obsessions in photography: to stop a place/ location in time, to “rescue time from its proper corruption”.3

I became drawn to the almost forensic photographic practice of Patrick Ronald and Shannon McDonell not only from an uncomplicated enjoyment of their very complicated representational methodology and its results, but by the fact of their emotional connection to places: specifically to Australian country towns, which form a large part of their shared experience as young artists who have chosen to work outside of city-centres and hubs of contemporary practice. Their first attempts at a kind of measured exactitude in photography, called MICROCOSM in 2005 were further developed as part of a series of responses within a longer-term project called Disappearing Tasmania: An Image of the West which commenced in 2006. This year-long project took an interactive approach to documenting towns that had been transformed by shifting agricultural practices and economies, through both photographs of abandoned buildings and abodes, photographic portraits and in-depth interviews with each location’s remaining inhabitants.

The artists’ photographic representations of buildings in country towns shared something of the objective and aesthetically unfettered practice of German photographic duo Bernd and Hilla Becher, who began working together in the late 1950s on a typological project documenting disappearing German industrial architectures and engineered structures. Their famous series of black and white images of water towers stood out among examples of formal modernist photography, for the palpable sense of distance they achieved and attention to difference within a seemingly mundane range of subjects. Where the Becher’s approach relied on calculated distance, Ronald and McDonell’s process relied on a calculated proximity, with each photograph of buildings from the artist’s various series being constructed from hundreds of close range images digitally stitched back together. The effect of this process was a kind of uncanny flattening, which represented the building as floating free of its surroundings, without the sense of perspective and depth that one can usually distinguish in photographic images taken from a single vantage point. Shown together, and often to scale, the range of buildings, from small houses, to local shops, to post offices to large warehouses, revealed the scale and scope of economic change and its impact on basic services and the ability of a town to function as a community.

Habits and Habitat is a micro-to-exact photographic extension of the artists’ deepening concerns with change in communities and places that have previously been defined by their relative stability. The project re-presents selected elevations of rooms in a working farmhouse in NSW, in two-dimensional 1:1 scale, like a small corner of the map of Borges’ unnamed empire. As a house that has remained largely unchanged for many years (save the necessary upgrades in entertainment and other technologies), it stands in opposition to the nature and appearance of city-based properties, as markets revolve increasingly around temporary occupation, cosmetic and structural renovation, and speculation. Viewing the kitchen image, with its original fittings and the texta-drawn graph accumulating the standing heights of loved-ones and visitors, it seems like we are being shown a projection from the past; a fragment from a time when people remained in one place, and followed a path firmly established by the generation that preceded them.

In this domestically reflective series, juxtaposed within the CarriageWorks’ post-industrial ambience, we are able to peer across (and almost into) a flattened scene, wherein walls, objects and the dust that occasionally settles on them, are given equal visual weight. Resisting the qualities that one could associate with ‘good’ photography, Ronald has taken thousands of evenly-spaced, evenly lit and equidistant photographs of each room, leaving the digital piecing-back together of the elevations to McDonell (amusingly reflected by the jigsaw image of the Mona Lisa shown hanging on the wall of the house’s living room). Through this apportioned methodology, the artists seek to undermine both visual hierarchies and the illusory qualities of photomedia. We see the image as a whole, from a distance, but its flatness and non-compliance with linear perspective forces us to look closer, to take in the details and to read the images with the same proximity and level of intimacy as they were originally taken. Though pseudo-scientific in nature, borrowing from archaeological photography I view Habits and Habitat as an attempt to take a measure and a resonance of domestic spaces that have held the lifetimes of their occupants, but are yet fragile and will, in time, disappear.

Ronald and McDonell’s work is processual in ways that are both epic in terms of scale and quantity of visual data, and also minute and painstaking in detail. From a small country town in NSW, the artists work in a micro-realist modality that is rooted to an emotional connection to the places from which they collect their images. Rather than tourists or day-trippers in their commitment to exactitude in representation, the duo is rather firmly entrenched in rural Australian habits and habitats.

Bec Dean, Associate Director, Performance Space

1 This single paragraph, On Exactitude in Science was written by Borges in 1946 and attributed falsely by the author to Suarez Miranda, 1658. Various sources.

2 Baudrillard, Jean, trans. By Sheila Faria Glaser, Simulacra and Simulation, The University of Michigan Press, 2003, pp. 1

3 Bazin, André, trans. By Hugh Gray “The Ontology of the Photographic Image,” Film Quarterly, 13, 4, 1960, pp. 8

Habits & Habitat

Patrick Ronald & Shannon McDonell

Patrick Ronald was born 13th November, 1980, in Sydney, NSW, Australia. He studied photography at Charles Sturt University, Albury NSW, from 1999 to 2003. Shannon McDonell was born 7th October, 1981, in West Wyalong, NSW, Australia. She studied photography at Charles Sturt University, Albury from 2001 to 2004 where she met Patrick Ronald. The two artists first collaborated in 2005, and have worked together since then.

From their first series of photographs MICROCOSM- Launceston Heritage Study, 2005, the artists have not veered from architectural and portrait works that employ intricate digital manipulation to create highly detailed images. Their first major documentary undertaking was Disappearing Tasmania: An Image of the West in 2006 where they were given their first grant to live on the West Coast of Tasmania and conduct an intensive survey project to try an illustrate what it is that creates and sustains a community and what visible evidence there is of a towns decline. Since then they have moved towards more manipulated works such as the m2 series which was designed to investigate visual perception. This work was a clinical representation of 50 spaces, both interior and exterior, within the artists’ personal habitats that they had occupied throughout their lives. Learning from the m2 project and the experiences they had gained, the couple has now embarked on their most ambitious project to date Habits and Habitat, two years in the making, where they will reconstruct sections of a house in 1:1 scale and immerse viewers within the image.

Artists’ Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the Payne family for enduring weeks of interruption and for giving us all a chance to visit their home. Thanks also to Performance Space, particularly Bec Dean, for giving us the platform to attempt such an ambitious project, and to our supporters VFX, Nikon Australia and Kayell Australia who made this production achievable.

Performance Space is supported by The Australian Government through the Australia Council, its arts funding and advisory body and the New South Wales Government through Arts NSW. Performance Space is supported by the Visual Arts and Craft Strategy, an initiative of the Australian, State and Territory Governments

Open for Inspection

ELIZABETH STANTON

The cathedral-like central hall of Sydney’s CarriageWorks (a former-rail-yard-turned-cultural-precinct in the city’s inner west) is an unusual place to find a typical Australian farmhouse. The photographic installation Habits and Habitat by NSW-based artists, Patrick Ronald and Shannon McDonell made this juxtaposition of space and place possible, transporting the domestic interior of a rural home to the heart of the post-industrial site in two dimensions. The work not only acquainted inner city viewers with an overlooked rural reality but also explored the documentary possibilities of the photograph in the digital age.

Across eight large-scale inkjet prints, installed as a series of almost theatrical backdrops through which visitors could wander-a working NSW farmhouse is reproduced on a 1: 1scale.Walking onto the ‘set’ of someone’s bedroom, kitchen and living room,1 felt like a virtual trespasser curiously perusing the private spaces, traces and belongings of an absent family. The very lived-in rooms are shown in immaculate detail: Ronald takes thousands of equidistant images of every inch of the home, and McDonell digitally pieces them back together. The effect renders visible the dust settling on the furniture, the patterns in the bedspread, the texture of the papers on the shelves, the views into other rooms and the contrast of the sun-drenched landscape beyond the windows.

This work follows previous collaborations by Ronald and McDonell including MICROCOSM-Launceston Heritage Study (2005) and Disappearing Tasmania: An Image of the West (commenced 2006), as well as their own individual practices that have seen the artists use photography to document evolving social histories in regional areas. Throughout Ronald and McDonell’s work there is echoes of Walker Evans’ and Dorothea Lange’s famed documentation of agrarian poverty (for the US Farm Security Administration’s photography program,

1935 -1944) mixed with what Charlotte Cotton described as the ‘deadpan aesthetic’ of the masters of architectural detail, Andreas Gursky and Candida Hofer. Against the history of the medium, Ronald and McDonell use digital post-production to explore the possibilities new technologies offer in freezing time and space for closer scrutiny. •

While providing an impressive amount of visual information, the painstaking level of detail that Ronald and McDonell achieve curiously does not grip the viewer in an empathetic closeness to this particular family’s home. In the micro-observation and exactness there is a sense of emotional detachment. This is perhaps heightened by the flattening of perspective created by the digital manipulation. There is no immediately readable ‘point of view’ as the viewer, I see everything at once, finding myself also positioned 1:1 with the image. The contents of the home become the guide to a trace of the human-the marks on the kitchen wall measuring the height of family members, the photographs within the photographs providing a sense of history.

In describing the artists’ process, curator Bee Dean notes, ‘Though pseudo-scientific in nature, borrowing from archaeological photography, I view Habits and Habitat as an attempt to take a measure and a resonance of domestic spaces that have held the lifetimes of their occupants, but are yet fragile and will in time, disappear’.’

In this way the work investigates our awareness of rural habitats on the verge of change, and perhaps even extinction. The Federal Government’s Australia 2020 Summit report on rural Australia (May 2008) painted a picture of an aging, diminishing population with significantly less access to physical and social infrastructure than their urban counterparts. The report noted a ‘deep concern that urban Australia mostly holds a negative perception that is thought to be inhibiting remote, rural and regional Australia’. Habitats and Habitat opens a door for us to see a side of rural NSW that contrasts how we’ve come to know it from media reports laden with youth suicide and drought. The artists reveal a realm not too dissimilar on the inside to our own urban domestic cocoons. While the lighting is bright, the mood is not overwhelmingly optimistic, and as I follow the growth of this family in the height chart on the kitchen wall I wonder what the future holds.

Patrick Ronald and Shannon McDonell’s Habits and Habitat, curated by Bec Dean, was held at the Performance Space at CarriageWorks, Sydney from 11 February to 17 March 2010.

- Charlotte Cotton The Photograph as Contemporary Art (London: Thames & Hudson,2004) 81.

- Bec Dean Habits and Habitat, catalogue published by Performance Space, Sydney, 2010.

3· ‘Future directions for rural industries and rural communities’ in Australia 2020 Summit: The Final Report (Published by the Department of Prime Minister and Cabinet, ACT,2008) 91.

POIMENA ART AWARD

From June 29, 2007 to July 23, 2007

The winner of the $5000 Poimena Art Award for 2007 is a collaboration between Patrick Ronald and Shannon McDonell for their a large photographic print entitled M2 – Bathroom 1.

The Poimena Art Award is a biennial acquisitive prize for mixed media work. It has been running since 2003. Any artist working in Australia or overseas can enter. Artists are required to respond to a particular theme. In 2007 this is the notion of ‘Shine’. This theme conjures uplifting thoughts of light and joy as well as the notion that ‘all that glistens is not gold’. The theme therefore, is open to an endless range of creative possibilities which is what this award is all about.

The judges Kristin Headlam and Raymond Arnold described the work as:

“A clever response to the theme of the award – ‘Shine’. It is ostensibly about glistening bathroom surfaces but as you look further the shine has been burnished off by life embedded in the detritus and dust.

The work is contradictory. After the initial double take, the viewer is overwhelmed by the sheer formal beauty of it. There is a refined sense of arrangement, colour, form and pattern which is the framework for human experience.

Truth, reality and representation are held in tension – a highly constructed artifact which expresses the artists’ ideas about the dignity of the every day. They have created beauty out of the every day, achieving a dignity and an austere purity.”